MambaPM is a process model matching tool for BPMN, PNML and EPK processes a process matching system. Our approach is based on a two-layer correspondence derivation process. In the first phase, we generate numerous correspondences attached with confidence scores. Therefore we firstly identify correspondences based on well-known NLP techniques focusing on the syntactical structure of the activity labels. Secondly, we generate correspondences employing automatic semantic role labeling to the activity labels based on the lexical database FrameNet in combination with distributional semantics by DISCO. After obtaining the correspondences of this approach, we retrospectively delete correspondences in such a manner, that additionally structural information of the process model is exploited and the remaining correspondences maximize an optimization problem according to structural restrictions.

Generating highly accurate process model alignments is a difficult task, however, large amount of work has been put there to increase the matching algorithms. In this paper, we present a process model matching algorithm employing classical NLP as well as more sophisticated semantic role labeling techniques. Instead of solely relying on semantic role labeling, we incorporate a fuzzy component achieved by distributional semantics. Afterwards, the process model alignments based on both syntactic and semantic matching strategies are cleaned using Markov Logic in combination with structural restrictions on the correspondences.

This section briefly introduces the fundamental concepts and frameworks used in our presented process matching system. Therefore, we explain distributional semantics and present a corresponding java-based implementation we used in our experiments. Afterwards, we introduce the main notion behind semantic annotation using the FrameNet [1, 5, 7] framework.

In general, distributional semantics is about harvesting large text corpora and producing word vectors as a result. Multiple word vectors form a word space. Based on these vector representations of words, we can compute semantic sim- ilarities between words. It exploits the fact that similar words occur in similar contexts. For our process matching system we particularly employ DISCO [6] allowing us to compute the cosine similarity between two words based on a precomputed word space.

The FrameNet project is building a lexical database consisting of thousands of manually annotated sentences trying to facilitate and improve the semantic analysis of words in sentences for machines. This framework is build on the notion of frame semantics. Basically, the meaning of words can be understood best if placed within a semantic frame describing for instance the events or participants. Such a semantic frame consists of multiple smaller fragments, called frame elements. A lexical unit evokes a frame and often provides the basis for detecting the surrounding components in the text which belong to a specific frame element.

The figure above shows an example sentence annotated with semantic frames from the FrameNet project. In this example, the sentence is annotated with four distinct semantic frames. For example, the first frame is called Sending and was evoked by the word 'send'. The Sending frame consists of the core frame elements Goal, Recipient, Sender and Theme. In addition, this frame consists of multiple other non-core frame elements such as the Container in which something is sent. However, in our example only the Theme and Goal frame elements are contained and assigned to the appropriate parts of the sentence. Thus, we discover that an acceptance letter(Theme) is sent(Sending-Frame) to an student(Goal). Note that the student not only belongs to the frame element Goal of the Sending frame but also itself evokes the frame Education Teaching which refers to teaching or participants in teaching. For our process matching system, we use SEMAFOR [4, 3, 2] since it is an implementation for automatic semantic role labeling based on FrameNet. It is trained with machine learning techniques and generates semantic frame annotations also for unseen sentences.

This section introduces \mamba, a process matching system combining semantic parsing using FrameNet [1] and distributional semantics using DISCO (extracting DIStributionally related words using CO-occurences) [6]. We divide the process model alignment into two separate layers. The first layer is responsible for generating correspondences attached with a confidence value, by the means of both syntactic as well as semantic analysis of the activity labels. Hence, this layer is completely agnostic in terms of the underlying structure of the process model and only generates alignments based on the comparison of activity labels. Afterwards, the generated alignment is used as input to the second layer which is responsible for identifying and removing previously created correspondences in such a way that the confidences are maximized subject to predefined rules. These rules introduce structural restrictions between activities. For example, is is very unlikely for similar activities to occur in completely different order. In the context of BPMN process models, a further structural restriction is, for instance, that two matching activities of a correspondence are likely to occur in the same swimlane.

The Figure illustrates the described two-layer process for generating alignments. The illustration contains abstractions of a BPMN process models, which neglects many important components of a process model, however, shows swimlanes and embedded activities as well as correspondences generated between two process models. Note that the main contribution of this paper is to present only the first layer in detail. However, the evaluation of the experiments also involves the application of the second layer.

The first and straightforward step for generating the process model alignment is achieved by identifying correspondences by syntactically matching activity labels. That is, we use well-known NLP techniques to preprocess the activity labels, and then generate the final correspondences by evaluating the string similarity and equality. This syntactic activity matching phase is capable of producing correspondences which are easy to identify. The basic NLP steps we apply to the activity labels are the following. First, we simply lower case all letters. Afterwards, we apply stemming of each word in the label to obtain the stems of the word. To produce the final correspondence, we check for string equality after applying all normalization techniques. Note that the appropriate confidence score of an identified correspondence is set to 1 manually, since we generate only correct correspondences with the described syntactic matching approach.

After applying the simple syntactic activity matching, the semantic activity matching component receives all remaining activity pairs. Hence, the characteristics of the activity pair the system tries to match are beyond the scope of simple syntactic matching. Therefore, we apply, as a second step, a more sophisticated semantic matching of the activity labels. To achieve this, we combine semantic annotation by FrameNet with distributional semantics. Incorporating distributional semantics in the frame generation process, at the same time incorporates a fuzzy component and facilitates to recognize correspondences which are semantically similar.

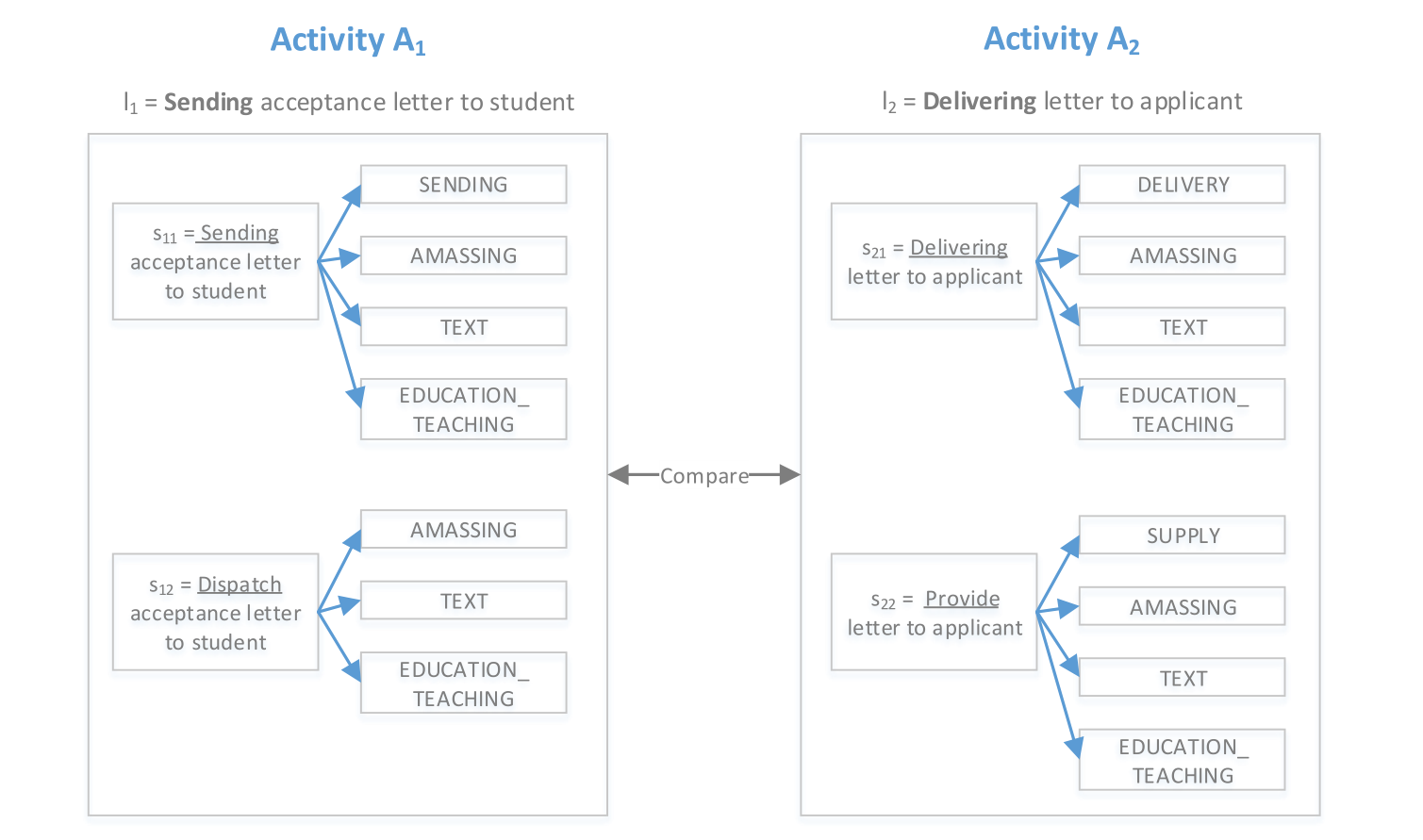

The Figure illustrates the general notion of semantic activity matching using FrameNet annotations. In the presented example, the semantic matching component tests whether activity A1 with the label l1 matches activity A2 with corresponding label l2, as we would typically observe in a university application process model. First of all, we apply POS-Tagging of the activity label to identify the verb. Afterwards, we generate k-many additional labels which are similar to the basic activity label, however, with its verb replaced by a similar word computed by the distributional semantics framework DISCO. We denote such a label by similar label s for the rest of the description. Note that the primarily label is a similar label trivially. The verb replacements are ordered descending based on the cosine similarity to the primarily label. DISCO also computes similar words which are no verbs. To identify and retain only similar verbs, we use the WordNet dictionary [9, 8, 10]. Each of the k similar labels are semantically annotated with semantic frames of FrameNet. Each similar label can trigger n-many frames. Overall we obtain k x n-many frames for each activity.

After deriving all frames following the procedure described previously for each of the two activities, we compare the resulting frame colletions. Here we use two distinct comparison strategies for generating the final correspondence between activity A1 and A2.

1. Single frame identical

If only one frame of the two frame collections is identical, we generate a correspondence C. The confidence score for C is computed as conf(C) = k / (k+1).

2. Majority vote frame identical

If the majority vote frame of each of the two frame collections is identical, we generate a correspondence C. To compute the majority vote frame, we iterate over the k similar labels and increase the frame count for frame f, denoted as count(f), if a frame was triggered at the current similar label. Hence, the maximum count for a frame is k, since a frame can only be evoked once per label. The majority vote frame f has the largest count(f) value among all produced frames. Note that the majority vote frame is actually a frame set, since different frames can have the same maximum count. If we obtain two majority vote frame sets, only one frame of them is required to be equal to generate a correspondence C. The confidence score for the generated correspondence C is computed as conf(C) = min(count(f1),count(f2)) / (k+1) with f1 being the majority vote frame of activity A1 and f2 being the majority vote frame of A2.

The figure above shows an explicit example taken from a set of university application process models. The two activity labels involved are semantically very identical, however, the simple syntactic matching component is not able to detect the correspondence. Let frame number parameter k = 2. Since 'Sending' is identified as the verb in l1, we generate the two similar labels. As the first similar label, we use the primarily label itself. To derive a second similar label, we replace 'Sending' by 'Dispatch', which has a high cosine similarity according to DISCO. For these two similar labels, three equal frames are evoked which are Amassing, Text and Education Teaching. However, the Sending frame is only triggered for the first label. Hence, we obtain count$(Text) = 2 and count(Sending) = 1 for activity A1. Therefore, the majority vote frame set consists of the three frames having a count of 2. The majority vote frame set for activity A2 is identical to the previously described one. Finally, we generate the correspondence C between A1 and A2 with conf(C) = 2/3.

Even semantically identical labels can yield wrong correspondences if we are blind to the underlying context of an activity. In the context of BPMN process models, one context of an activity is given by the swimlane the activity is embedded in. We denote this swimlane context by SWC for the rest of the paper. Thus, matching not only activities but also the corresponding context potentially increases the number of correctly identified correspondences. The fundamental notion of context-aware activity matching is to combine both activity matching as presented previously, and the appropriate SWC matching. So far we investigated only activity matching, however, we can easily adapt this approach to SWC matching. Since swimlanes often also contain labels, we simply apply the same matching strategy between the different SWCs. For computing the final confidence score for correspondence C including the context, we use the harmonic mean between the activity confidence denoted by cA, and the SWC confidence denoted by cSWC. We use lambda as a weight to balance importance between the two confidence scores.

If lmbda = 0, then the confidence score is equal to the score without considering the context. However, if lambda > 0, then lambda describes the importance tradeoff between the initial activity matching and context matching. That is, high lambda biases the final confidence score to the context confidence score between the two contexts involved, whereas low lambda biases the final confidence score to the actual activity confidence. To compute these confidence scores, the algorithm presented previously is applied. Note that this context matching is allowed only to decrease the activity confidence. That is, having highly similar activities but at the same time only low context similarity, reveals probably rather dissimilar activities. However, having high context similarity but low activity similarity is not implying higher activity similarity. Note that there are cases where the SWC label is missing. If at least one of the two SWCs involved appear to have a missing label, the final correspondence generation simply falls back to only matching activities.

The Figure presents the abstract representation of two process models and correspondences between them. If we assume large lambda and high activity confidence scores for the shown correspondences, the final confidences scores are also only high if we obtain high context confidence scores between context correspondence SWC11 and SWC22, and context correspondence SWC12 and SWC21, respectively.

This section presents the evaluation and results of our proposed process matching system on a well-known process model benchmark. We applied MambaPM on BPMN process models describing the application process for students at nine different universities. Thus, we generated 36 alignments between the different process models and evaluated them in terms of precision, recall and f1-measure. Since we have two individual layers in the correspondence generation process, we show precision, recall and f1-measure for both components denoted by pre-in, rec-in, f-in for the first layer and pre-out, rec-out and f-out for the second layer producing the final score.

The Table presents the results achieved using only the syntactic matching component as well as the two proposed frame collection comparison strategies with both syntactic and semantic matching applied. In addition, we evaluated on multiple parameter settings for k and the confidence threshold. Note that for the majority vote comparison method, we only included the results for k = 20, since for larger k the results are identical. For the single frame comparison, we provide only results without an applied threshold, since this strategy only generates two distinct confidence scores. Applying a threshold to remove correspondences with the lower confidence score simply retains the correspondences of the syntactic matching component with confidence of 1. For the single frame comparison, we tested different k values and included only the best two, which is k = 1,3.

Applying only the syntactic matching component for generating the alignments results in a f1-measure of 0.588. Since we generate simple correspondences based on syntactical analysis, we do not forward the results to the second matching layer. Note that the pre-in < 1 for this test case, because some trivial correspondences are not included in the goldstandard. Investigating this result, we reveal that nearly 44% of the correspondences in the goldstandard are easy to identify correspondences by applying syntactic matching. We observe that in general the pre-in is very low for the single frame as well as the majority frame comparison. However, the rec-in is high for majority vote without threshold and above all for the single identical frame comparison. Since the semantic matching component is not much restrictive in terms of generating correspondences, we expected high recall but on the other hand also higher precision. Not that the second matching layer produces considerably better result by applying structural debugging of the previously generated alignments. Here, single frame comparison achieves best f1-score of 0.42. Without debugging, the majority vote comparison scores best with a f1-score of 0.205. In addition, the experiments revealed that for majority vote comparison, the parameter k has only low influence to the results, but at least to the produced confidence scores.

Note that we also conducted the evaluation incorporating the context matching, however, the results are identical to the results shown in the Table without applying the context matching. This is due to the fact that often either no context correspondence can be generated at all, or the context correspondence has a confidence value which is greater than the confidence of the activity correspondence. Hence, the final activity correspondence is not changed most often. Note that the context matching can only reduce the confidence scores of activity correspondences, which could produce more valuable confidence scores for the second structural debugging layer.

The experimental evaluation revealed that our process matching system MambaPM is in general capable of generating correspondences based on syntactic analysis using NLP, but also correspondences which are more difficult to identify and beyond the scope of simple syntactical activity matching. Subsequently, this leads to a higher recall, however, results in a vast loss of precision. That is caused by the vast number of correspondences the matcher derives, being not restrictive at the semantic matching component. For example, the matching system generates the following three correspondences:

Since we solely rely on a general semantic frame comparison, the matcher produces two wrong correspondences by plainly identifying the Sending frame. Although each of involved activities appear to have a semantic similarity (in all activities something is sent to someone), we miss important information by neglecting the comparison of the individual frame elements. Often, the automatic semantic role labeling based on FrameNet evokes frames based on the verbs as lexical units. If that is the case, we reduce semantic correspondence generation to simply comparing verbs using the proposed comparison strategies.

Since the second layer in the process model alignment generation involves solving an optimization problem based on the previously generated correspondences, we observed another important finding. The first syntactic and semantic matching layer is required to generate reliable confidence scores. At the moment, the algorithm produces correct correspondences with low confidences and vice versa. Thus, we strive for producing accurate and more varying confidence scores.

[1] Collin F Baker, Charles J Fillmore, and John B Lowe. The berkeley framenet project. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and 17th International Conference on Computational Linguistics-Volume 1, pages 86–90. Association for Computational Linguistics, 1998.

[2] Dipanjan Das, Desai Chen, Andr´ e FT Martins, Nathan Schneider, and Noah A Smith. Frame-semantic parsing. Computational linguistics, 40(1):9–56, 2014.

[3] Dipanjan Das, Nathan Schneider, Desai Chen, and Noah A Smith. Probabilistic frame-semantic parsing. In Human language technologies: The 2010 annual confer- ence of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics, pages 948–956. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2010.

[4] Dipanjan Das, Nathan Schneider, Desai Chen, and Noah A Smith. Semafor 1.0: A probabilistic frame-semantic parser. Language Technologies Institute, School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University, 2010.

[5] Charles J Fillmore and Collin Baker. A frames approach to semantic analysis. 2010.

[6] Peter Kolb. Disco: A multilingual database of distributionally similar words. Pro- ceedings of KONVENS-2008, Berlin, 2008.

[7] Meghana Kshirsagar, Sam Thomson, Nathan Schneider, Jaime Carbonell, Noah A Smith, and Chris Dyer. Frame-semantic role labeling with heterogeneous annota- tions. people, 3:A0, 2015.

[8] Claudia Leacock and Martin Chodorow. Combining local context and wordnet similarity for word sense identification. WordNet: An electronic lexical database, 49(2):265–283, 1998.

[9] George A Miller. Wordnet: a lexical database for english. Communications of the ACM, 38(11):39–41, 1995.

[10] Ted Pedersen, Siddharth Patwardhan, and Jason Michelizzi. Wordnet:: Similarity: measuring the relatedness of concepts. In Demonstration papers at HLT-NAACL 2004, pages 38–41. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2004.